Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Ethical Issues Main Page | Political Issues Main Page

| Religion Main Page

Chapter 1: What is Philosophy?

The only way for a person to understand philosophy is to be confronted with the various philosophical questions, to become familiar with the philosophical positions, and to contend with the philosophical issues for oneself.

There are four ways to approach the meaning of philosophy:

1. To consider the word itself,

2. to examine the various fields of philosophy,

3. to view it as a rational, critical enterprise, and

4. to consider its differing conceptions or forms.

The Word Itself

Philosophy is derived from a Greek word meaning love of, or pursuit of wisdom.

The Fields of Philosophy

Philosophy contains several fields or areas of investigation. Although there are other areas that might be considered, the author describes six including:

1. Metaphysics - the study or theory of reality,

2. Epistemology - the study or theory of knowledge,

3. Value-theory - the study of value in all its manifestations,

4. Ethics - the study of moral value, i.e., what is right and wrong, moral principles, etc.,

5. Aesthetics - the study of the value of art and the concept of beauty, and

6. Logic - the formation of the principles of right reasoning. Logic is the tool philosophers use to investigate the issues.

A Rational, Critical Enterprise

Philosophy is a rational and critical enterprise. A rational argument makes sense, is coherent, and well-founded. Philosophy seeks to eliminate perspectives of ignorance, superstition, prejudice, blind acceptance of ideas, and any form of irrationality. However, not everything can be reduced to an argument or expressed in language. There is perhaps nonrational knowledge or intuition. Some philosophers believe that all knowledge rest on fundamental truths that are not subject to any proof. This is referred to as Foundationalism.

Differing Conceptions or Forms

The different forms of philosophy include:

The Speculative - tries to answer the most ultimate questions, i.e., what is reality, what is the ultimate good, etc.,

The Analytic - takes linguistic analysis or analysis of language as the task of the philosopher, i.e., to unravel and to clarify philosophical language. It is based on the view that most disagreements in philosophical studies are due to an attempt to answer questions without first precisely defining the question.

The Existential - understanding the most fundamental question of philosophy, i.e., the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.

A Working Definition

"Philosophy is the attempt to think rationally and critically about the most important questions." However, the various forms indicated above indicate that there are different ideas about what philosophers should think rationally and critically about.

Philosophy, Religion, and Science

Religion is a slippery word. Religion is similar to philosophy in that it considers such things as the ultimate reality, the meaning of life, good and evil, and human nature. Religion includes beliefs about these things that are defined in a fairly systematic and fixed manner, but not in as rational and critical manner as philosophy. A religious individual is bound to something, usually understood to be God, and the worship of God including rituals and ceremonies. This reflects the existential nature, as opposed to the intellectual character of religion.

Science, on the other hand is the study of something. Some view theology as a science, but most people think of science in terms of the social sciences (sociology, psychology, anthropology, etc.), or the natural sciences (physics, biology, chemistry, astronomy, etc.). Science, like philosophy involves the pursuit of knowledge, but its focus is more restricted to the natural world alone, and its method is more restricted to the tools of observation and experimentation.

Of Beards and Bread

The phrase "Philosophy bakes no bread" is an expression indicating the view that philosophy is irrelevant or useless. To many people it might seem that philosophy has little to do with our work, or our views on politics, abortion, capital punishment, bank loans, love, death and other day to day things that we experience. However, what we think about ourselves, the physical universe, religion, value, and right and wrong determines how we actually live in the world. Everything we do is dictated in some way by our views about these remote things. Thinking critically about the questions that really matter is part of being human. "The beard does not the philosopher make," i.e., in a sense we are all philosophers.

William James (an American philosopher) suggested that we fall into two camps, the tender-minded and the tough-minded. The tender-minded views reason as the source of knowledge, based on intellect and ideas. The tough-minded views the five senses as the source of knowledge based on the world of science and facts. The tender minded accepts the spiritual dimension of our existence, and tends to be a person of conviction and belief, while the tough-minded finds no evidence of the "spiritual" and suspends judgment to wait for more evidence. Some may be part tender-minded and part tough-minded. This book will help the reader determine which philosophical inclinations they have.

Where Do We Begin?

In another essay (The Will to Believe) William James introduced the idea of "living options" and "dead options." Living options are ideas that fit with our previous ideas, beliefs, and experiences. Dead options on the other hand, are ideas that do not fit with our previous beliefs and experiences. We begin with living options, and move out from there.

As indicated Chapter 1 logic is the tool philosophers use to investigate the issues. Some view logic as the key to philosophizing. Although the science of logic is broad and complicated involving uses of language, types of propositions, types of arguments, construction and use of symbolic languages, probability theory, and more, the purpose of this chapter is simply to introduce the reader to some of the basic elements of logic.

The Three Laws of Thought

The three laws or principles that make thought and discourse possible include:

1. The Law of Non-Contradiction - Nothing can both be and not be at the same time in the same respect.

2. The Law of the Excluded Middle - Something either is or is not.

3. The Law of Identity - Something is what it is.

Technically the principles are identical, but they address different issues. A statement is either true or false and it cannot be both at the same time in the same respect. However, a statement can be true at one time and false at another time, but it cannot be or not be anything at the same time.

What is An Argument?

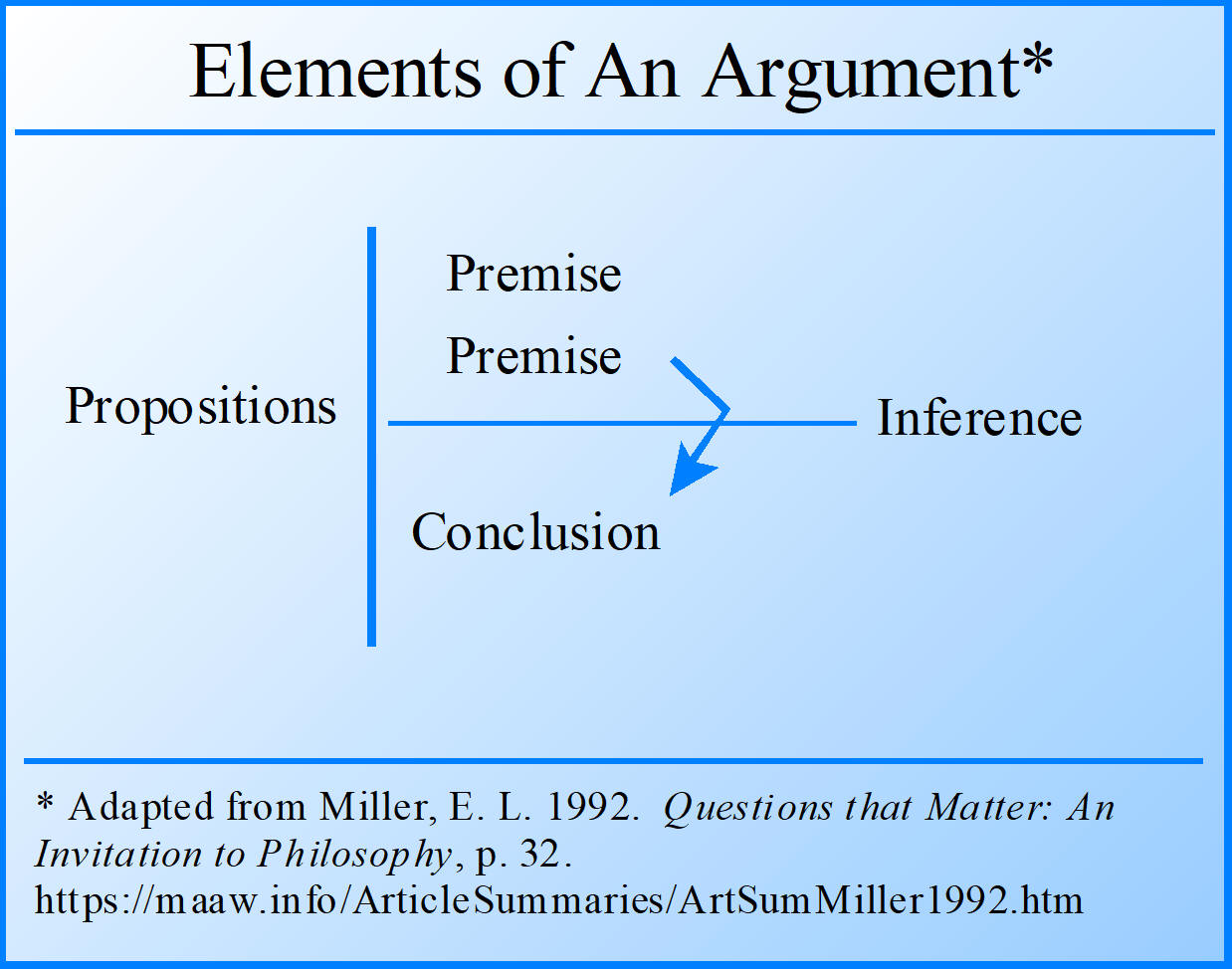

An argument is an attempt to indicate that something is true by providing evidence to support it. An argument includes a group of propositions where one follows from at least one other. The propositions that provide the evidence are premises, and the proposition that follows from the premises is the conclusion. The connection that causes the conclusion to follow from the premises is an inference or entailment.

Deductive arguments reason from the whole (general) to the part (specific), while inductive arguments reason from the part (specific) to the whole (general). In a valid deductive argument the premises guarantee the conclusion. In a good inductive argument, the premises suggest that the conclusion is probably true.

Deductive Reasoning

A valid argument form makes an argument valid and the most common form of deductive argument is the syllogism. A syllogism consist of two premises and a conclusion, and there are three kinds of syllogisms: Categorical, Disjunctive, and Hypothetical.

I. Categorical Syllogism - the premises are propositions about classes of things and they affirm or deny that one class is included in another class. For example: All X are Y. All Y are Z. Therefore, all X are Z. There are four forms of categorical propositions:

Form 1. Universal affirmative, e.g., All X are Y.

Form 2. Universal negative, e.g., No X are Y.

Form 3. Particular affirmative, e.g., Some X are Y.

Form 4. Particular negative, e.g., Some X are not Y.

There are six rules that cannot be violated for a categorical syllogism to be valid.

Rule 1. It must contain exactly three terms that are used in the same sense throughout the argument.

Rule 2. The term present in both premises, but absent in the conclusion must be distributed, i.e., refer to all members of the class in at least one premise. Invalid example: All X are Y. All Z are Y. Therefore, all Z are X.

Rule 3. If either term is distributed in the conclusion, it must be distributed in the premises. Invalid example: All X are Y. Some Z are not X. Therefore, some Z are not Y.

Rule 4. It cannot have two negative premises. Invalid example: No X is Y. No Z is Y. Therefore, no X is Z.

Rule 5. If either premise is negative, the conclusion must be negative.

Rule 6. A syllogism with a particular conclusion cannot have two universal premises.

II. Disjunctive Syllogism - has a proposition that poses alternatives (disjuncts), indicated by either or.

Rule. A valid disjunctive syllogism must include a denial of one alternative while the conclusion affirms the other.

III. Hypothetical Syllogism - the premises contain a hypothetical or conditional proposition, and antecedent and consequent, i.e., "if... then."

Rule: In a valid hypothetical syllogism, the first premise and the conclusion have the same antecedent, the second premise and the conclusion have the same consequent, and the consequent of the first premise is the same as the antecedent of the second premise.

Mixed Hypothetical syllogisms include one conditional premise and one categorical premise, e.g., Premise If X, then Y. Premise X. Conclusion Therefore, Y.

Rule 1: Any mixed hypothetical syllogism is valid if the categorical premise affirms the antecedent of the conditional premise, and the conclusion affirms its consequent.

Rule 2: Any mixed hypothetical syllogism is valid if the categorical premise denies the consequent of the conditional premise, and the conclusion denies its antecedent.

An argument is valid if it conforms to a valid argument form, but validity and truth are different. An argument can be valid when every proposition is false. For example: All politicians are Communists. Babe Ruth is a politician. Therefore, Babe Ruth is a Communist.

An argument can be invalid when every proposition in the argument is true. For example: All U.S. presidents have been males. Abraham Lincoln was a male. Therefore, Abraham Lincoln was a U.S. president.

A sound deductive argument is one that has a valid argument form and has premises that are true.

Inductive Reasoning

No inductive argument can be demonstratively certain. A strong inductive argument is one where, if the premises are true, the conclusion is probably true by virtue of the supportive inference. Inductive arguments can be based on a generalization, or an analogy.

Generalization - For example: There are several instances of where A is observed to be X. Therefore, all A is X.

Analogy - can take different forms. For example: A, B, C, and D are observed to be X and Y. M is observed to by X. Therefore, M is Y.

Informal Fallacies

Informal fallacies are mistakes in reasoning due to carelessness in terms of relevance and clarity of language, i.e., fallacies or relevance, and fallacies of ambiguity.

Fallacies of relevance include:

1. Appeal to force. Employing threat, intimidation or pressure.

2. Appeal to the man. Abusive irrelevant attacks on the person making the claim rather than the claim.

3. Appeal to the man. Calling attention to irrelevant circumstances.

4. Appeal to ignorance. Affirming the truth of something based on a lack of evidence to the contrary.

5. Appeal to the crowd. Using an emotional appeal to the passions and prejudices of the listeners.

6. Appeal to pity. Arousing pity and sympathy for the plight of someone.

7. Appeal to authority. Appeal to an irrelevant authority.

8. Begging the question. Circular reasoning occurs when the conclusion is disguised in one of its premises.

9. Accident. Applying a general to a specific situation.

10. Converse accident. Generalizing on the basis of an inadequate number of instances or atypical instances.

11. False cause. Confusing an effect of a condition with the cause of that condition.

12. Complex question. Posing a question that can be answered only on the basis of an unasked question.

Fallacies of ambiguity include:

1. Equivocation. When a word or expression changes its meaning in the course of an argument.

2. Amphiboly. Ambiguous grammatical construction that can be understood in two ways.

3. Misplaced accent. Emphasizing a word or expression, or omitting relevant information to mislead.

4. Composition. Attributing the parts of a whole to the whole itself.

5. Division. Attributes the characteristics of the whole to the parts.

_______________________________

Go to the next Chapter: Chapter 3: The Metaphysicians

Related summaries:

Hornsey, M. J. and K. S. Fielding. 2017. Attitude roots and Jiu Jitsu persuasion: Understanding and overcoming the motivated rejection of science. American Psychologist 72(5): 459-473. (Summary).

Kenrick, D. T., A. B. Cohen, S. L. Neuberg and R. B. Cialdini. 2018. The science of antiscience thinking. Scientific American (July): 36-41. (Summary).