The Question of God: Summary of Chapters 12-15

Study Guide by James R. Martin, Ph.D., CMA

Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida

Chapters 1-2 |

Chapters 3-7 |

Chapters 8-11 |

Chapters 16-19 |

Chapters 20-22

Introduction to Part Three

When considering the question of God, the author recommends that the reader try to lay aside prejudices, mental blind spots, and wishful thinking. However, this is very difficult to do because we all tend to assimilate information in a biased way that reinforces what we already think. This is referred to as the principle of motivated reasoning discussed by Hornsey and Fielding in one of the article summaries listed at the end of this summary.

Natural Theology

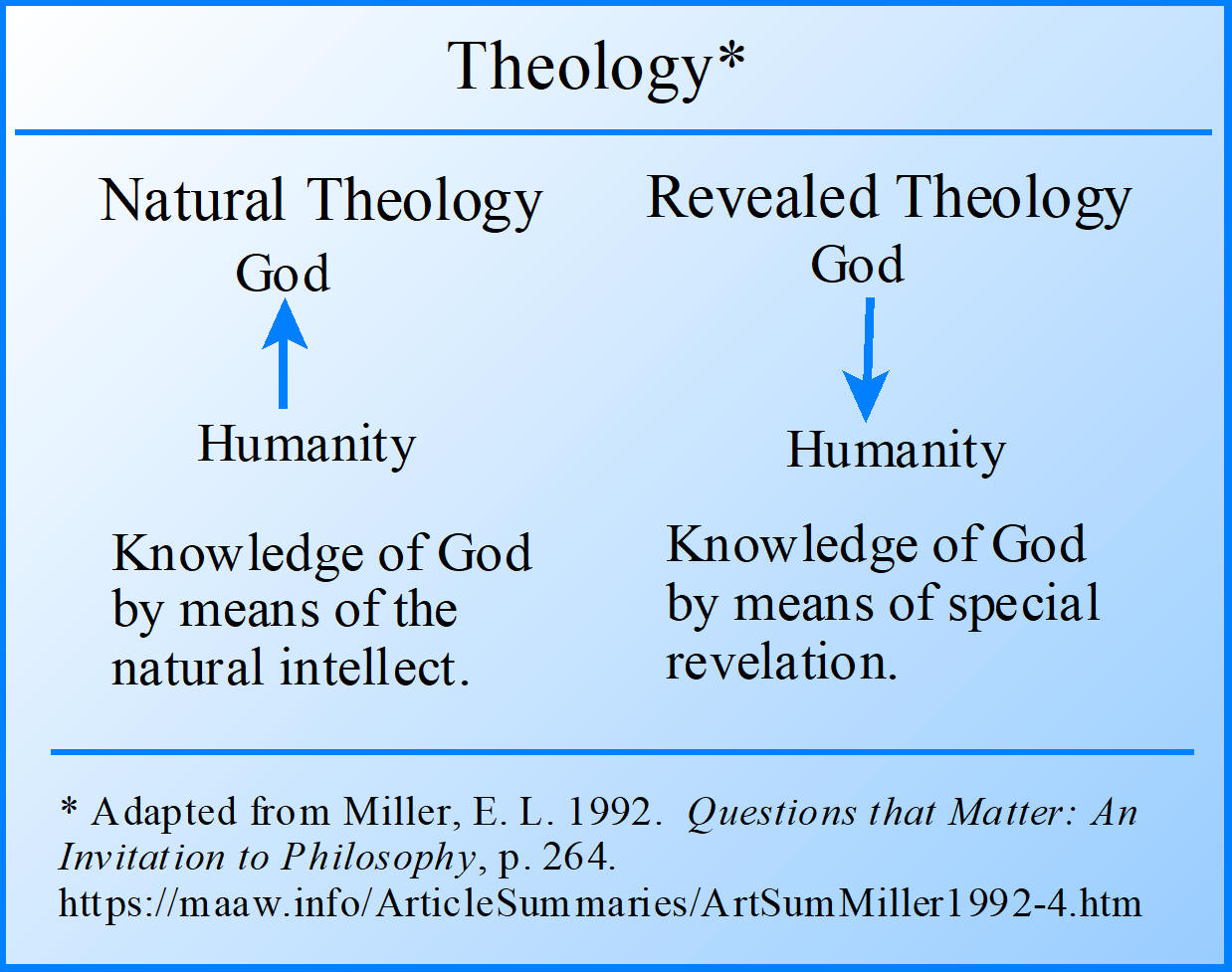

Theology is the study (some would say science) of, or knowledge of God. Natural theology refers to the study of the knowledge of God acquired through the intellect. Revealed theology refers to knowledge of God acquired through special revelation, such as the Bible, the Church, Moses, Christ and the Holy Spirit. Revealed theology, if true, would provide a knowledge that bears on human salvation.

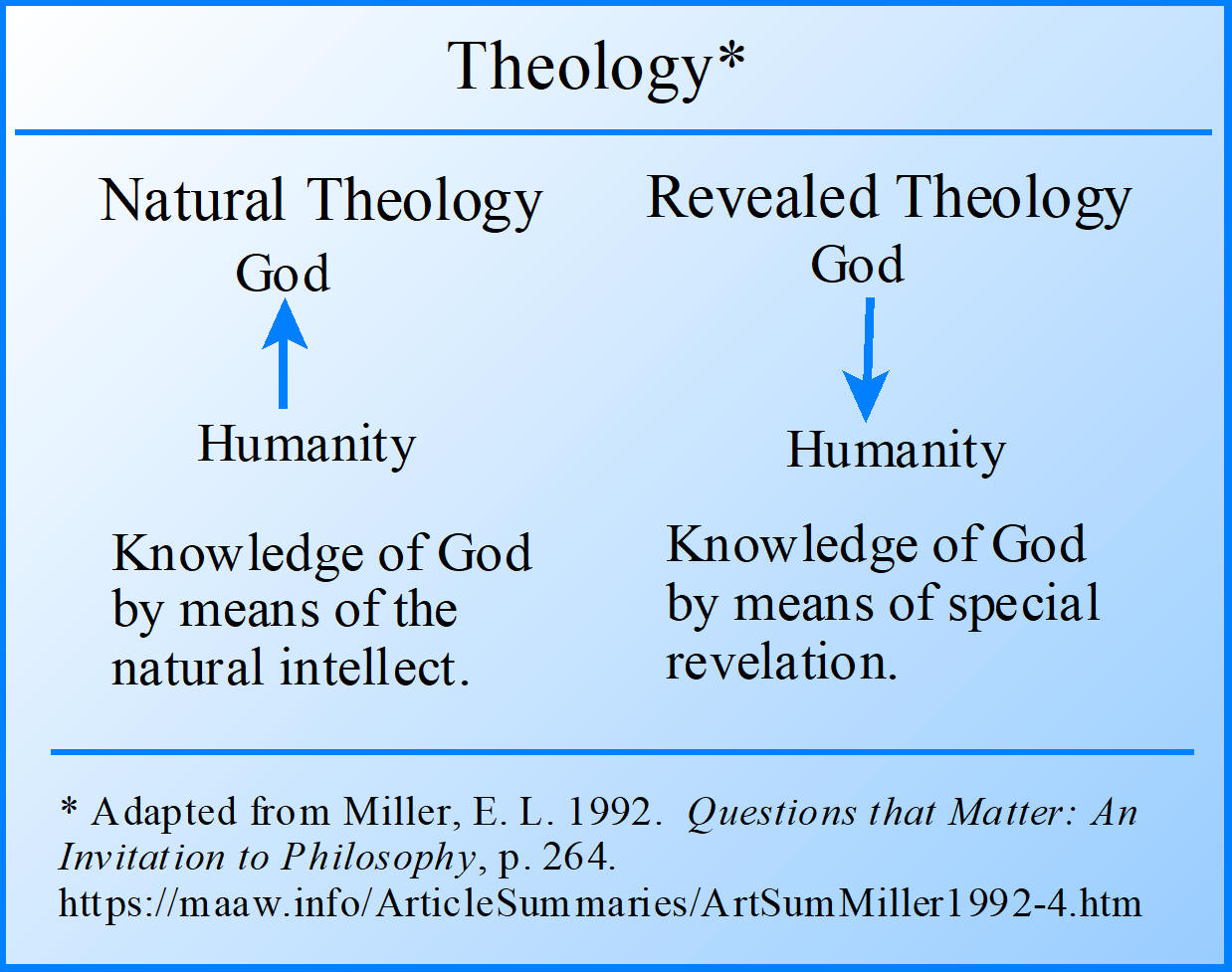

Chapters 12 and 13 raise the question of God's existence and include some of the best known arguments pro and con. Two posteriori arguments are presented in Chapter 12 including the Cosmological Argument and the Teleological Argument. This is followed in Chapter 13 by two a priori arguments, the Ontological Argument and the Moral Argument.

The Cosmological Argument

The cosmological and teleological arguments for gods existence are based on the idea that knowledge of God can be derived from sense experience (a posteriori). The term cosmos comes from the Greek word for world. The cosmological argument is that there has to be a God because there must be a first cause of everything in the cosmos. The argument is expressed as follows:

"All contingent (or caused) being depends for its existence on some uncaused being.

The cosmos is a contingent being.

Therefore, the cosmos depends for its existence on some uncaused being."

St. Thomas Aquinas provided five proofs or ways to show Gods existence:

1. Whatever is moved is moved by another. A thing cannot both be mover and moved. Therefore, there must be a first mover, moved by no other. This must be God.

2. There is no case known where a thing is found to be the efficient cause of itself. Therefore, it is necessary to admit a first efficient cause. This must be God.

3. We find in nature things that can be and not be. If everything can not-be, then at one time there was nothing. Therefore, we must admit the existence of some being not receiving it from another. This must be God.

4. There is gradation found in all things, i.e., more or less of everything. There must be something that is truest, best, noblest, something that is the most being. Therefore, there must be something that is to all beings the cause of their being, goodness, and every other perfection. This must be God.

5. Natural bodies that lack knowledge act to obtain the best result. They must be directed by some being endowed with knowledge and intelligence. Therefore, some intelligent being exist that directs natural things to their end and this we call God.

Underlying each of these proofs is the idea that everything needs a cause. There must be some ultimate being that the world depends on for its existence.

According to the Big Bang theory, the present expanding universe points to a moment about fifteen or twenty million years ago when all the matter in the universe was condensed and exploded. Some have identified this as the origin of the universe in support of the cosmological argument. The new story of Genesis.

The Teleological or Design Argument

The teleological or design argument is that God is the only adequate explanation for the order, purpose, unity, harmony, and beauty of the cosmos. The cosmos is designed in such a way that it must be a product of mind. William Paley (1743-1805) used an inductive watch analogy to argue that the human eye demands an intelligent creator just like a fine watch that must have had a maker. According to Paley, "The eye proves it without the ear, the ear without the eye."

Paley's watch analogy became irrelevant after 1859 when Darwin published the Origin of Species. Paley, and practically everyone else before Darwin believed that the universe, humans, and everything else had all been created all at once. Darwin's doctrine of gradual evolutionary development delivered a deathblow to Paleyan teleology. Darwin explained how life evolved over long and progressive sequences of natural causes and effects. The human species and the rest of the biological and physical universe could be explained in naturalistic terms.

Although Darwin's theory of evolution has been associated with atheism, it did not deal a deathblow to God. According to F. R. Tennant (1866-1957) the evidence of evolution supports the view that the narrow teleology of Paley should be replaced with a wider or cosmic teleology. Evolution or gradualness is no proof of the absence of external design. Theistic evolution is instead the belief that God uses natural evolutionary processes to bring about the desired effects.

The Problem of Causality

The cosmological and teleological arguments for God have been criticized in many ways. The author provides only two for us to consider.

1. Some have asked, "If everything has a cause, then what caused God?" Miller argues that this question misses the point because not everything must have a cause. Only every event or thing that comes into being must have a cause. God, according to the cosmological argument is not an event or something that comes into being. God is instead an uncaused transcendent or supernatural being. This is the idea that God is distinct from the universe and beyond human cognition and thought.

2. Another troublesome feature of the cosmological and teleological arguments for God is the idea that every event must have a cause. Hume and Kant both questioned whether the concept of causality may relate to anything beyond the sensible world. According to Hume we have no rational reason to ascribe to a transcendent being the idea of causal activity that we know only from our limited experience of the sensible world. According to Kant, it is not possible to ascribe to God the concept of causality because it is a principle of sense experience and therefore has no application beyond sense experience.

This chapter considers two a priori arguments, the Ontological Argument and the Moral Argument. The ontological argument is based on the idea of God, while the moral argument is based on the idea of moral law. Both of these arguments for God's existence are based on the idea that knowledge of God can be derived from reason.

The Ontological Argument

The ontological argument begins with the definition of God as the greatest or most perfect possible being conceivable, and that it is greater to exist objectively, in reality than subjectively in the mind. Therefore God must actually exist, because if God did not exist, God would not be the greatest being possible. This argument has been stated by many philosophers including St. Anselm (1033-1109) in his Prologium, and Rene Descartes in Meditations on First Philosophy.

Critics asked how we could possibly derive the real existence of something from the mere idea of it. Advocates of the ontological argument think that misses the point because they consider existence as a defining property, attribute, or predicate of God. Attacks against this view claim that existence is not a predicate. In Critique of Pure Reason (1966), Kant argued that "Being is evidently not a real predicate, or a concept of something that can be added to the concept of a thing."

In Knowledge and Certainty (1963) Norman Malcolm agreed with Kant's criticism but said St. Anselm had two arguments. The first argument revolves around the idea that God is a greater being if he exists than if he does not exist. But the second argument revolves around the idea that God is a greater being if he "cannot not-exist." Then necessary existence is a divine property, attribute, or predicate. Malcolm's ontological argument is summarized as follows:

God is an unlimited being.

The existence of an unlimited being is either impossible or necessary.

The concept of an unlimited being is not self-contradictory, so such a being is not impossible.

Therefore such a being is necessary.

The Moral Argument

The moral argument is based on our experience of moral reality, not our experience of empirical reality. The author begins this section by making a distinction between moral laws and moral law.

Moral laws are the particular, changing, and relative views that human beings formulate about morality. Our moral conscience reflects these views.

Moral law refers to our moral consciousness or belief in morality itself apart from our views of it. Moral law, if it exists is grounded in an adequate source or Lawgiver.

The moral argument is as follows:

If there is an absolute moral law, then there must be an absolute mind as its basis.

There is an absolute moral law.

Therefore, there must be an absolute mind as the basis of the moral law.

There have been many advocates and variations of the moral argument for God. C. S. Lewis in Mere Christianity (1967) argued that there have been differences in the moralities of Egyptians, Hindus, Chinese, Greeks, and Romans, but their moral views were all very similar to each other. No one admires those who are selfish, run away in battle, or double cross the people who have be kind to them.

Hastings Rashdall (1858-1924) in The Theory of Good and Evil (1907) set out to establish a theoretical justification for moral law. According to Rashdall, moral law does not exist in the mind of this or that individual, but only in a mind that is the source of whatever is true in our own moral judgments, i.e., "in a Mind from which all reality is derived." "In other words, objective Morality implies the belief in God."

Is There a Moral Law?

The moral argument cannot work without an objective and absolute morality, i.e., moral law. So the issue is between moral absolutism and moral relativism:

Moral absolutism - morality is independent of the individual.

Moral relativism - morality is relative to the individual.

The major evidence for moral relativism is the wide variety of differences that exist from person to person, and from culture to culture. It is the view that morality is nothing more than perceptions, desires, inclinations, or tastes of an individual person, community, or society.

There is an interesting debate about this issue between Bertrand Russell and Frederick C. Copleston at the end of this chapter. Copleston defends the absolutist position, and Russell defends the relativist position. Copleston argues that man has a consciousness of obligation and of moral values, a criterion of right and wrong that is obtained from the ultimate values established by God. Russell argues that moral law is not absolute, it is always changing, and what one believes is essentially what they have been told by their parents and others. Conduct that is right is what would probably produce the greatest possible balance in intrinsic value of all acts possible in the circumstances. A person has to consider the probable effects of their action to determine what is right. This controversial question is addressed again in Chapter 16: Challenges to Morality.

Chapter 14: Religious Experience

The religious experience approach to God is nonrational, but not irrational. In other words, those who advocate religious experience as a way to obtain a knowledge of God view religious experience as superior to knowledge obtained through reason or experience. In The Idea of the Holy Rudolf Otto (1869-1937) explained that the rational approach was wrong and a one-sided interpretation of religion. His idea was that the nonrational view is at the center or core of authentic religion. This core is the sense or awareness of something, a kind of sensation, or presence that is holy, overpowering, and divine. Otto called it a "numinous feeling" or feeling of the divine reality and presence.

The Mystical Ascent

Mystical experience is an interesting experimental way of seeking knowledge of God. In The Doors of Perception (1970) Aldus Huxley described a sort of instant mysticism when one takes mescalin (a psychedelic hallucinogen) under supervision. The person's ability to think straight is not significantly reduced, but their visual impressions are intensified. According to Huxley they loose interest in space and time and focus on the value and meaningfulness of existence, a shortcut to religious or heightened consciousness. Mysticism is defined as "the pursuit of a transcendent, unitive experience with the absolute reality."

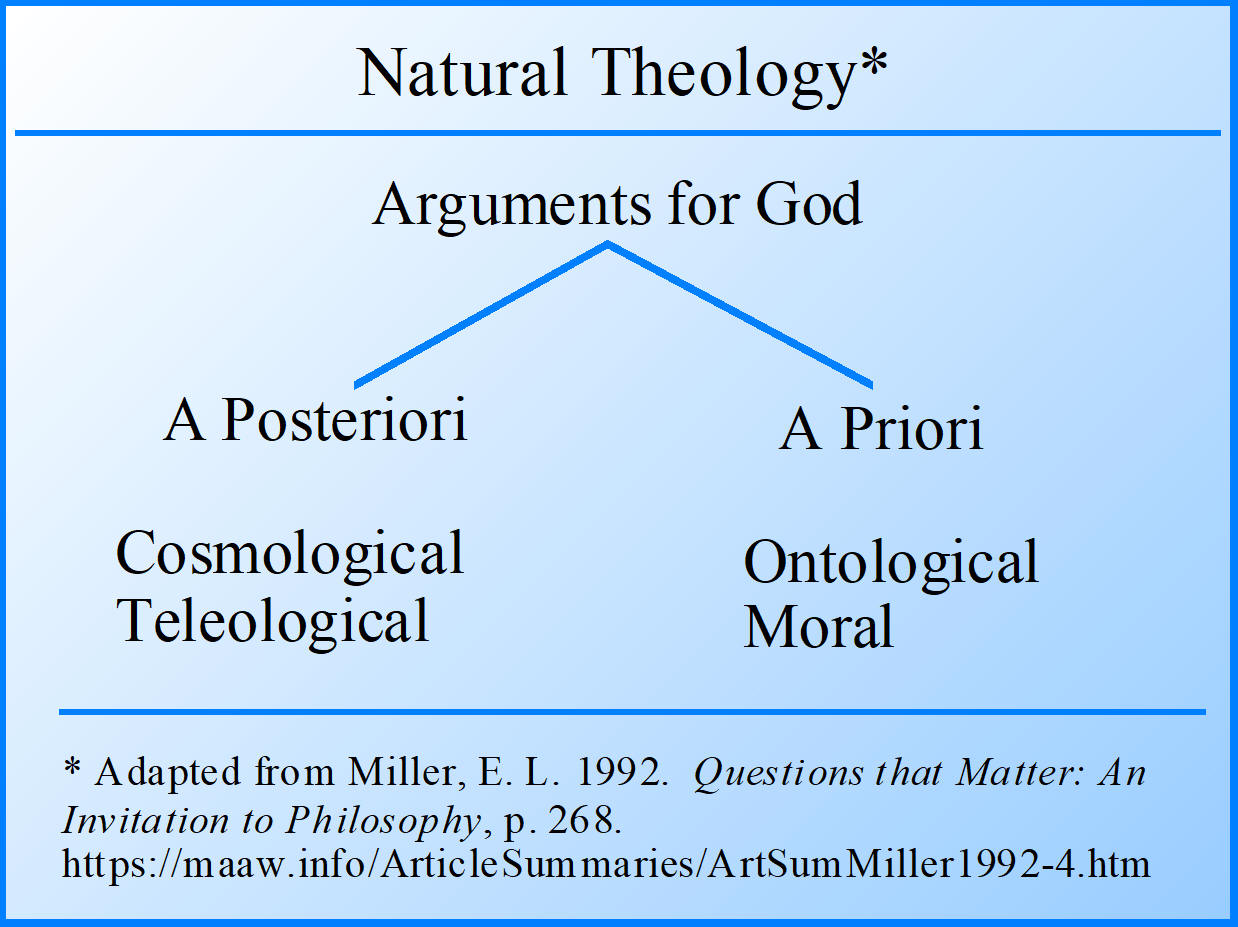

Classical mysticism, as opposed to Huxley's description above is interested in emptying the consciousness of all sense impressions and ideas so that the soul may attain a different reality of a higher nature. The idea is similar to Plato's ladder or scale of being, described in the Allegory of the Cave discussed in Chapter 4. The basic steps are illustrated in the graphic below. One moves from the sensible world of images, to the intellectual world of ideas, to pure self-consciousness, to beyond self or to the soul standing outside, to God, goodness, and light.

Western mystics including Christians, Jews, and Muslims do not mean a literal union with God, but instead, according to St. John of the Cross (1542-1591) the soul becomes a window to the divine light, will, and love. St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582) referred to it as a "spiritual marriage" with the divine. An individual engages in a progressive struggle to attain heightened levels of spiritual existence resulting in an "indescribable mystical union."

Mysticism East

Eastern mystics including those in China, India, and Japan are said to be more spiritualist than the Western variety. Although both East and West share many images in describing their religious experiences, Eastern mystics believe in the unity of the being and for them the mystical union is a literal unity of the individual with the ultimate reality. Their view is that it is a unity that has always existed, but is discovered in mystical illumination.

The Way of Zen

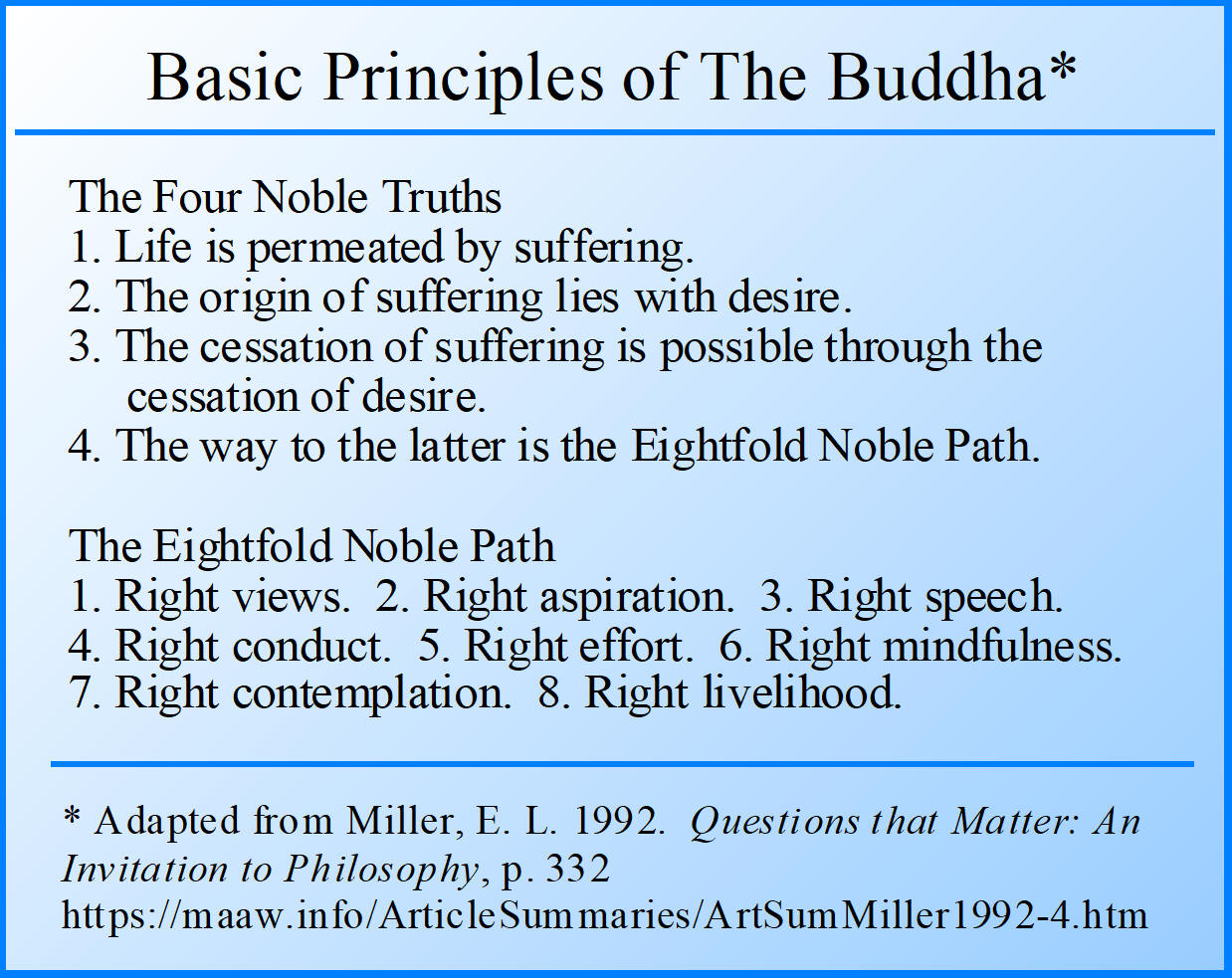

This section begins with the story of Buddha. Around 560 B.C. Gautama was miraculously conceived and at birth became a future Buddha. When he reached the age of 29 he ventured out from an overprotected wealthy family environment and was shocked by the suffering he encountered. As the story goes he sat under a sacred Bodhi Tree vowing to remain until he attained enlightenment. Finally enlightened he preached a sermon disclosing Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Noble Path. Buddhism seeks to penetrate the indescribable Emptiness beneath, behind, or beyond things, a kind of healing, or balancing, or harmonizing of our distorted minds and emotions.

Zen (meditation) Buddhism supposedly provides a way to achieve the enlightened state. It starts with meditation in the yoga position, and involves breathing exercises and the contemplation of a riddle or paradox, e.g., what is the sound of one hand clapping. The second step involves additional exercises designed to break down the difference between the sacred and secular. The aim is to reach the Zen experience of Satori, a sudden and illuminating enlightenment that overtakes the successful disciple. According to Zen Buddhism, Satori is not seeing God as he is, but seeing the work of the creation, i.e., "an intuitive looking into the nature of things in contradistinction to the analytical or logical understanding of it."

The Tao

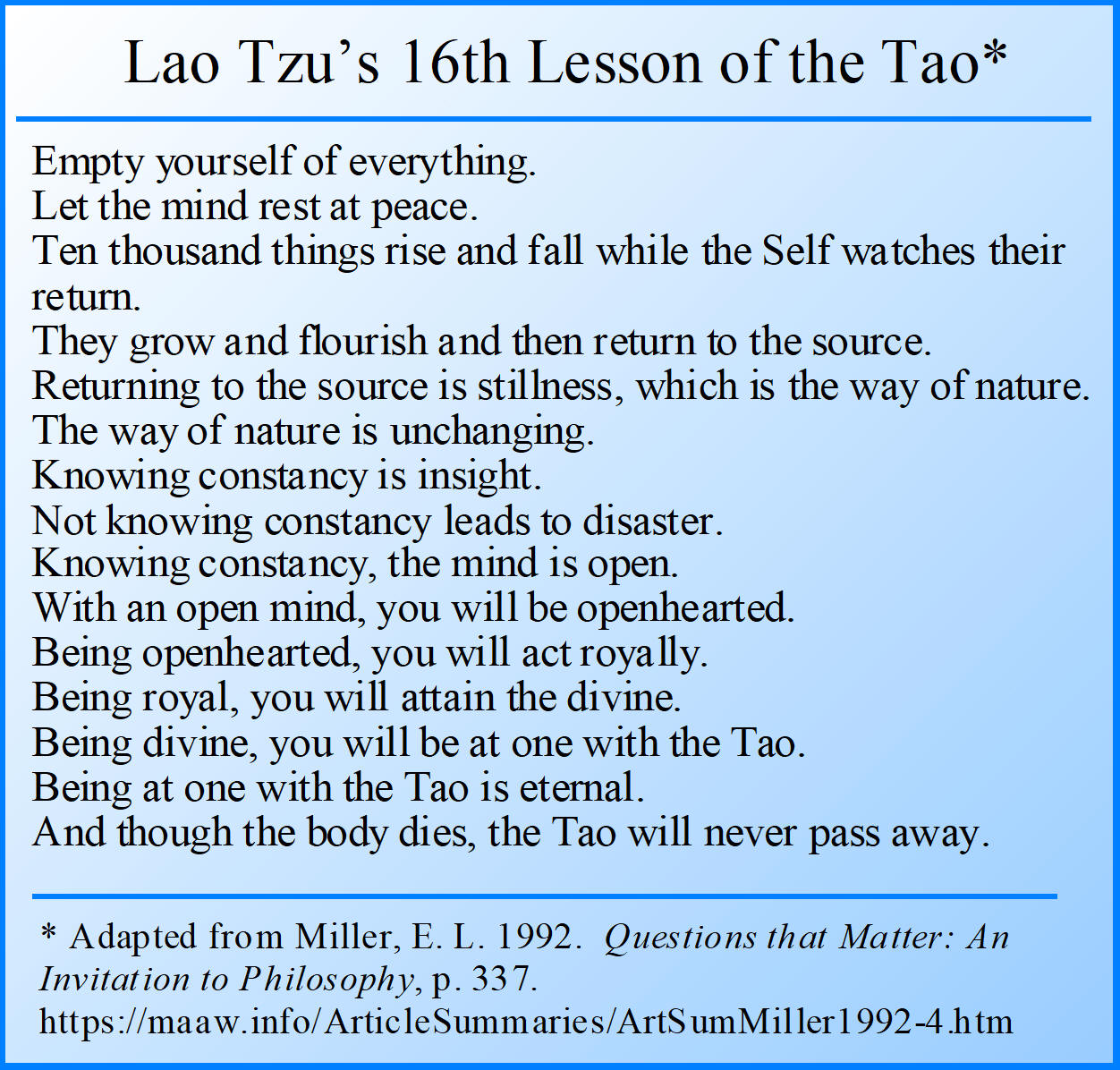

The "Wisdom of China" is mainly attributed to Confucius (fifth century B.C.) and Lao Tzu (sixth century B.C.). Confucius was concerned with the conduct and ordering of society, while Tzu emphasized an individual's participation in the Tao (The Way). His teachings included eighty-one lessons of the Tao te Ching. Tzu's sixteenth lesson is similar to The Way of Zen and is illustrated in the graphic below.

Is Religious Experience Evidence For God?

The personal or private nature of religious experience is perhaps decisive for the participant, but skeptics argue that the private nature of such experiences renders them sterile as objective evidence of God. Of course some philosophers disagree with this assessment of religious experiences. In Religion, Philosophy and Psychical Research (1953) C. D. Broad argued that when there is agreement between the way different people in different places, at different times, and different traditions interpret the cognitive content of these experiences, it is reasonable to attribute this agreement to their connection with a certain aspect of reality. These agreed upon experiences should be provisionally accepted as representing real events unless there is some positive reason for thinking they do not. In fact some skeptics have argued that such experiences may be explained as manifestations of physiological problems, sexual hang-ups, psychological abnormalities and other similar mental problems. In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) William James disputed this idea by accusing its proponents of simple-mindedly confusing the facts of mental history with their spiritual significance. Instead James stressed practicality, workability, usefulness, and consequences or results as the criteria of true beliefs. James believed that there is a religious reality, a conception of the supernatural that actually intrudes into and affects our world.

Is Religion an Illusion?

Criticisms of religious experiences that direct attention to the origin or causes of a belief, rather than its rational foundation involve a genetic fallacy. This is where a conclusion is unsupported by irrelevant facts. For example, in The Future of an Illusion (1964) Sigmund Freud attributed the origin of religious ideas to mankind's need for a father figure and a moral world-order that would ensure justice. Freud's view was that religious ideas presented as teachings are simply illusions, or fulfillments of this need. The author points out that those who attempt to explain away religious experiences as originating in psychological or physiological states provide cases of the genetic fallacy.

The argument against the existence of God on the basis of the evil in the world is perhaps the biggest stumbling block to the belief in God.

What is the Problem?

There are two types of evil: natural evil and moral evil. Natural evil is generated by natural causes, e.g., starvation, cancer, physical deformity, disease, earthquakes, floods, wild fires, tornados, hurricanes, etc. Moral evil refers to the evil that results from the human will, e.g., murder, torture, war, cheating, rape, exploitation, etc. The problem (called theodicy) is how to reconcile the evil in the world with a God who is supposed to be omnipotent (all-powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-loving).

In Three Essays on Religion (1874) John Stuart Mill rejected Christianity on this basis:

"Not even on the most distorted and contracted theory of good which ever was framed by religious or philosophical fanaticism, can the government of Nature be made to resemble the work of a being at once good and omnipotent."

In Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1948), David Hume stated the problem of evil and God in the following way:

"Is he willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil."

Believers do not accept the idea of a limited or finite God, or a malevolent or evil God. From a religious standpoint some have argued that God lies so far above us that it is impossible to understand why he allows evil to exist in the world. From a philosophical standpoint this argument is a retreat and unacceptable. One philosophical explanation is that it would be logically impossible to have a world without evil because anything created by God would have to be less than God, meaning less than perfect. Unfortunate things such as mishaps, accidents, disease, and famines are inevitable by-products of nature.

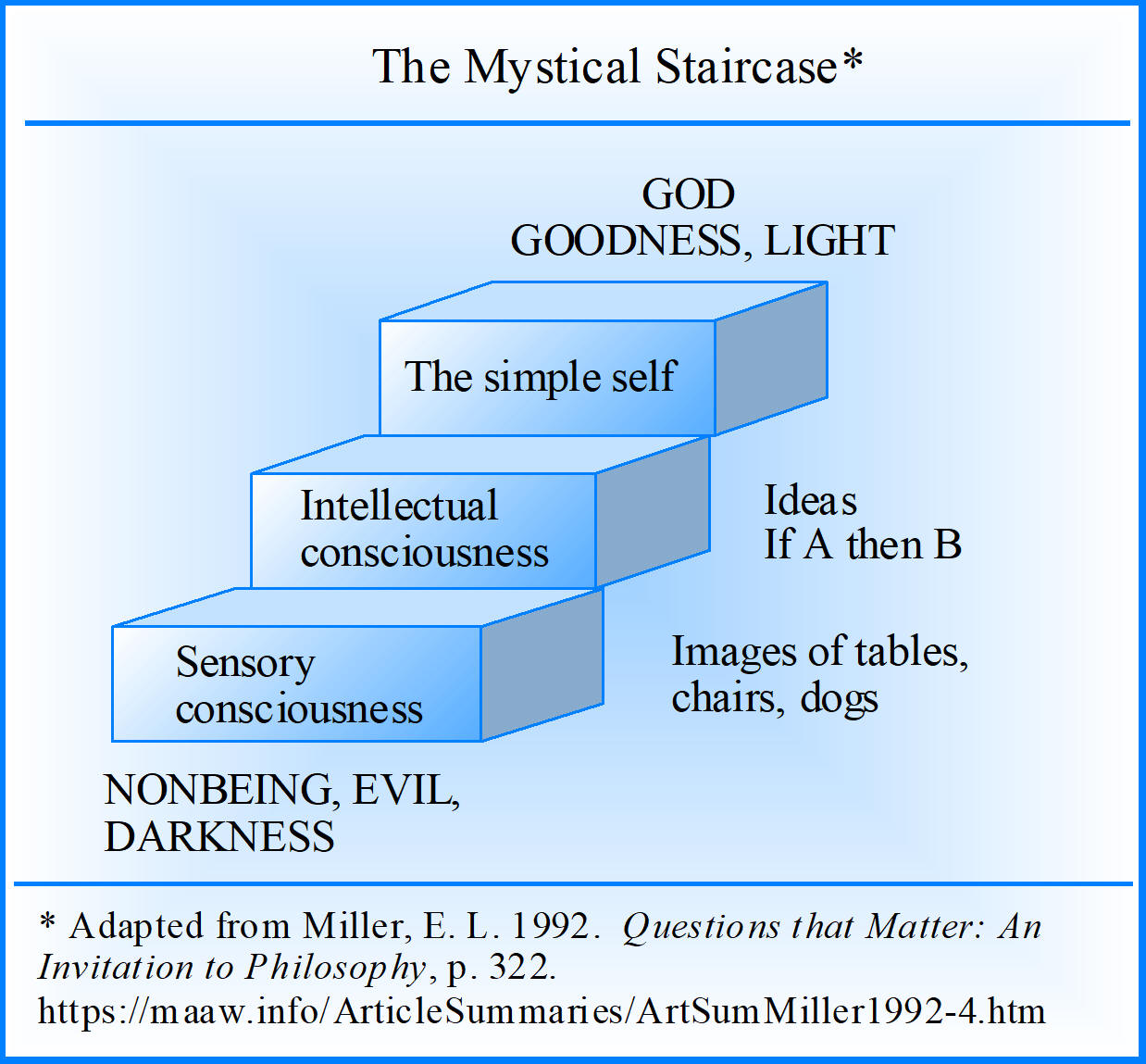

Evil as a Privation of Goodness

St. Augustine (354-430) denied that evil is a substance and called it the absence of goodness. He believed that the suffering caused by famines, disease, plagues and other natural evil is visited on human beings as just punishment for their sins. Moral evil, or sin may be traced to the absence of goodness. Just as disease is the absence of health in the body, sin is the absence of health in the will. The idea is that God is responsible for the goodness in the world, but not the nonbeing and evil. The privation of goodness argument is that while God is the highest being and the cause of all lesser being, he is not the cause of the relative nonbeing in the world.

The Free-Will Defense

In God, Freedom, and Evil (1974) American philosopher Alvin Plantinga made the following argument for the Free-Will defense:

"A world containing creatures who are significantly free (and freely perform more good than evil actions) is more valuable, all else being equal, than a world containing no free creatures at all. Now God can create free creatures, but He can't cause or determine them to do only what is right. For if He does so, then they aren't significantly free after all; they do not do what is right freely. To create creatures capable of moral good, therefore, He must create creatures capable of moral evil; and He can't give these creatures the freedom to perform evil and at the same time prevent them from doing so. As it turned out, sadly enough, some of the free creatures God created went wrong in the exercise of their freedom; this is the source of moral evil. The fact that free creatures sometimes go wrong, however, counts neither against God's omnipotence nor against His goodness; for He could have forestalled the occurrence of moral evil only by removing the possibility of moral good."

In Evil and Omnipotence (1971) British philosopher J. L. Mackie objected to the free-will defense and argued that God had the option to make human beings who would act freely but who would always choose to do good. His failure to so is inconsistent with his being both omnipotent and wholly good.

Evil as Therapy

In Evil and the God of Love (1978) John Hick explained an argument made by the Christian writer Irenaeus (130?-202?). The idea is that the experience of evil is a necessary part of the "soul-making" activity of God. Evil is the instrument God uses to correct, purify, and instruct his creatures to bring them to spiritual health and maturity. A problem with this argument is the difficulty of accepting the idea that all the death and suffering that occurs in the world is a divine means of spiritual progress.

Evil is Irrational

Another philosophical perspective is to abandon all hope of explaining evil and to see it only as evidence of the ultimate irrationality of human existence. This is the nihilistic perspective. Nihilism is the denial that values and ideals have any meaning or objective reality. Some atheists or humanists believe humanity is the ultimate reality. The problem with evil is not to reconcile evil with God (there is no God), but to reconcile evil with man (anthropodicy rather than theodicy). One way to do this is referred to as atheistic or humanistic existentialism that rejects most philosophizing as abstract and irrelevant, and emphasizes instead the business of living authentically. In The Myth of Sisythus and Other Essays (1955) Albert Camus argues that there are two extreme possible responses to the human condition: suicide (not recommended) and conscious revolt. We can at least recover something of human dignity by defying the irrational forces that will finally "do us in." Existentialism is considered again in Chapter 16.

_______________________________

Go to the next Chapter: Chapter 16.

Related summaries:

Dawkins, R. 2008. The God Delusion. A Mariner Book, Houghton Mifflin Company. (Summary).

Hornsey, M. J. and K. S. Fielding. 2017. Attitude roots and Jiu Jitsu persuasion: Understanding and overcoming the motivated rejection of science. American Psychologist 72(5): 459-473. (Summary).

Kenrick, D. T., A. B. Cohen, S. L. Neuberg and R. B. Cialdini. 2018. The science of antiscience thinking. Scientific American (July): 36-41. (Summary).

Martin, M. and K. Augustine. 2015. The Myth of an Afterlife: The Case against Life After Death. Rowland & Littlefield Publishers. (Notes and Contents).

Paine, T. 2006. The Age of Reason. The Echo Library. (Rebuff of church dogma originally published in 1796. Summary).

Prothero, S. 2007. Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know - And Doesn't. Harper San Francisco. (Summary).